Beginner Bass Base: Dynamic Grooves

MASTER BASS EDUCATOR PATRICK PFEIFFER HELPS BUILD EVERY ELEMENT OF YOUR PLAYING WITH HIS BEGINNER BASS BASE COLUMN

By Patrick Pfeiffer

ORIGINALLY POSTED IN BASS MAGAZINE, NOVEMBER 2019

Vilkommen to zis latest Pfeiffer column. Vat vill ve play today? Why, akzents, of course! Okay, let me drop this faux-German accent before my throat burns from rolling all the R’s. Accenting a musical note means striking it slightly harder than you do a regular note, making it louder. When you use dynamics, emphasizing and de-emphasizing notes within a musical phrase or groove, the music becomes far more interesting. It’s a fabulous tool for breathing life into grooves that would otherwise be too one-dimensional to excite your adoring fans.

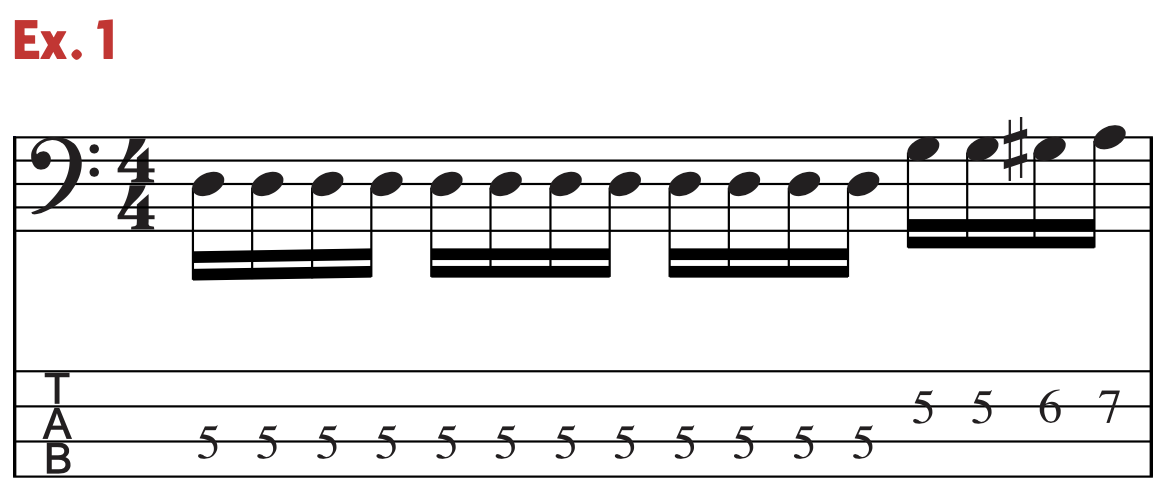

Take a look at the rather ordinary groove in Ex. 1. In this example, the root is played for three beats in a 16th-note rhythm, and then a little ascending line is added on the fourth beat. Every note is played at the same volume, and the only variation in the line comes at the end of the measure in the form of the harmonically ascending line. By adding dynamics in the form of accents and dead-notes, you can turn this ordinary groove into an extraordinary groove without changing any of the notes’ pitches. While accented notes are louder than the regular notes, dead-notes are softer. They’re more like a rhythmic “thud” with no pitch.

For the sake of this particular column, I use only regular notes, accented notes, and dead-notes in order to create the greatest contrast. Accented notes have a wedge-like symbol above them; dead-notes have an “x” in place of the note head.

Bass players routinely accent the first note of each measure as a natural way to reinforce the beginning of a phrase. But you need to be able to accent or deaden a note anywhere in a measure, even on the offbeats. Example 2 is an étude that helps you develop the ability to accent any note in a measure. Turn on a metronome and set it to about 60 beats per minute. Then play four evenly spaced notes for each click, which are 16th-notes. (If you need a refresher on this type of beat subdivi- sion, look at the Beginner Bass Base column in Bass Magazine Issue #4.) Now accent the first 16th-note of each beat, the one that coincides with the click, and keep the subsequent notes in the beat at normal volume. If you would like more contrast between the accented note and the regular notes, try playing the regular notes a bit softer so you don’t have to play the accented notes so hard. Example 2a gives you the proper picture.

Next, using the same tempo and the same notes, accent the second 16th-note of each beat. Keep all of the other notes at reg- ular volume. Check out Ex. 2b for this one. Continue by accenting the third 16th-note of each beat, as shown in Ex. 2c, and finally, accent the fourth 16th-note, as in Ex. 2d — all while maintaining the same tempo with the metronome. Practice these accents until you’re comfortable placing them on any 16th-note of a beat.

While accents are created with the striking hand, dead-notes are created mostly with the fretting hand. Play them by placing your fretting-hand fingertips onto the string without pressing the string onto the fretboard. Then strike the same string with your other hand, creating a pitchless thud. You need at least two fretting-hand fingers on that string to properly “kill” the pitch. Practice going back and forth between regular notes (with the fretting hand pressing the string to the fretboard) and dead-notes. The études in Ex. 3 help you develop this technique. Turn on your metronome, set to about 60 beats per minute, as before. Play four evenly spaced notes per click (16th-notes) at normal volume. Next, play a dead-note on the first 16th-note of each beat, followed by three 16th-note at regular volume, as shown in Ex. 3a. Once you’re comfortable doing this, move the dead-note to the second 16th-note of each beat (Ex. 3b), then the third (Ex. 3c), and finally the fourth 16th-note (Ex. 3d) — all while maintaining regular volume on the other notes.

The magic of using dynamics really kicks in when you combine accents and dead-notes along with regular notes in the same groove.Example 4 offers you insight into the interplay among the three note types. The accented notes are confined to the root of the groove, always repeating the same pattern throughout the first three beats. Example 4a shows the accent on the first two 16th-notes, Ex. 4b on the first and third 16th-notes, and Ex. 4c shows the accent on the first and fourth 16th-notes. The dead-notes are confined to the fourth beat, which consists of a chromatic line up to the 5th of the groove. Pay close attention to which notes to play as you move the dead-note from the first 16th-note to the second, the third, and final- ly, the fourth 16th-note. Notice that the pitches change to accommodate the musical flow.

I hope you enjoy your dynamic workout with these études and use them in some of the grooves you’re already playing. To hear how ultra-hip the use of dynamics is in real life, check out Jaco Pastorius’ groove on the chorus of “Come On, Come Over” [Jaco Pas- torius, 1976, Epic], or Gary Willis’ groove on “Otay” [Outbreak, 2002, Shrapnel]. These grooves are simply phenomenal and demonstrate to what extremes you can go in exaggerating the dynamic differences among regular notes, accented notes, and dead-notes — and make it sound oh so funky.

Until next time ... auf Wiedersehen!