Beginner Bass Base – Building Blocks Of A Groove: The Groove Tail (Part 3 of 4)

Patrick Pfeiffer continues his lesson series by breaking down one of the most important elements of groove: the tail

By Patrick Pfeiffer

ORIGINALLY POSTED IN BASS MAGAZINE, AUGUST 2021

Here is a tall tale to tell (pun-filled introduction, but you should be used to this by now): The third part of a great groove is the groove tail. It’s the most fun part, the sign-off, the least structured part, the freedom-loving revolutionary of the Three Groove-sketeers. It’s what you play at the end of your groove; it’s your signature lick, a sign-off for the preceding phrase, and a lead-in for the next phrase. It’s an opportunity for you to put a bit of a flourish into your groove (think John Hancock’s signature) and a place to prep the other band members for the next downbeat, making sure everyone is on the same page and in sync.

When you play the groove tail, you don’t necessarily have to adhere to the groove’s harmonic structure, as you do with the groove skeleton and groove apex (see the two previous issues of Bass Magazine). And you can vary your rhythm each time — you don’t need to keep it consistent. The only thing you must keep in mind is to be in time for the next downbeat! That’s it. Naturally, I just happen to have some great exercises to help you get used to creating a beautiful groove tail and nailing the downbeat on time.

The groove tail can be unpredictable and even inconsistent, so it would take up this entire issue to go through all of the possible choices you have for rhythms and notes — and that’s just for the 16th-note subdivision. Instead, let me show you fail-safe combinations that always work, whether you’re repeating the same chord you’ve just played (static harmony) or you’re moving to a new chord (mobile harmony).

Harmonically, the rule of thumb (and no, I’m not talking about slapping) is this: When you’re getting ready to repeat the same chord you’ve just played, make the last note of your groove tail the 5th of the chord. For instance, if you’re grooving on a C chord, play a G as the last note of your groove tail just before you return to the beginning of the next C chord. When you’re approaching a new chord, play the root of the previous chord as the last note of your groove tail. For example, if you’re playing a C chord and you’re getting ready to go to an F chord, play a C as the last note of your groove tail before hitting the F. Likewise, if you’re grooving on a C chord and you’re heading to a G chord, or an E chord — in fact, anything but another C chord — also play a Cas the last note of your groove tail.

Rhythmically, you have nine common possibilities for subdividing the last beat of the measure, the typical home of the groove tail: a quarter -note; two eighth-notes; four 16th-notes; two 16th-notes plus an eighth-note; an eighth-note and two 16th-notes; a dotted eighth-note and a 16th-note; a 16th-note and a dotted eighth-note; a 16th-note followed by an eighth-note and another 16th-note, and finally, three eighth-note triplets.

I’ve picked a groove that works fabulously well as a default groove over just about any chord in any style to practice the groove tail combinations (Ex. 1). I’ve left the last beat of the default groove blank (in the form of a quarter-note rest) — this is where the groove tail goes. Preceding each default groove is a real-life sample groove by a highly respected bass player, using one of the nine rhythmic groove tail possibilities. The sample groove is then followed by the default groove and a groove tail, either for repeating the same chord or for going to a different chord.

First, get that default groove (Ex. 1) under your fingers first and memorize it. This alone is useful to have in your toolbox. Now, time to wag that tail!

What would Paul McCartney do? Look no further than to Sir Paul’s iconic groove on the Beatles’ “Come Together.” A big, fat quarter-note with attitude is plenty for a powerful groove tail (Ex. 2a). To practice this using the default groove, work on Ex. 2b if you’re repeating the same chord and Ex. 2c if you’re going to a different chord.

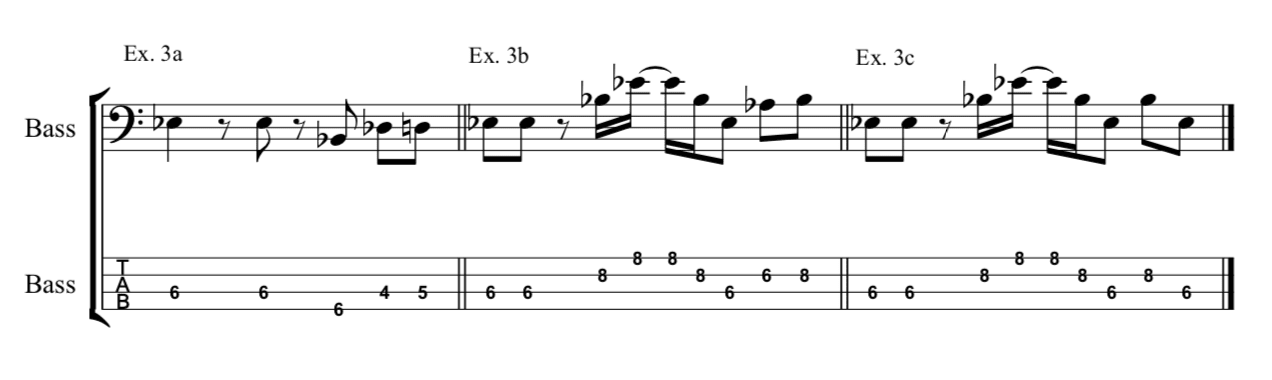

Another popular groove-tail choice is demonstrated by the fabulous Carol Kaye in the Lou Rawls classic “A Natural Man” (Ex. 3a): two eighth-notes smoothly lead to the next groove phrase … naturally. Again, Ex. 3b is for a static harmony, and Ex. 3c is for the move to a different chord.

The powerhouse of groove tails is the four-16th-note thriller. Jaco Pastorius rips through it in the muscular groove in “Come On, Come Over” (Ex. 4a). The workout groove using static harmony is shown in Ex. 4b and the groove for mobile harmony in Ex. 4c.

Wonder what Willie Weeks would want … as a groove tail, that is! Unearth the fantastic groove on Donny Hathaway’s live version of “Everything Is Everything”: two 16th-notes followed by an eighth (Ex. 5a). This bass line grooves so hard it makes you want to stay on the same chord just about the whole time … oh yeah, that’s right, that’s exactly what it does. The exercise for the static harmony is in Ex. 5b, and for mobile harmony it’s Ex. 5c.

Sometimes you hear a seriously cool bass part in a song you’ve heard so many times and wonder, who played it? It’s brilliant! Then you find out that the bass player is one of the unsung studio musicians who supplied terrific bass lines for a number of hits. In the case of the Hall & Oates hit “Sara Smile,” it’s Scotty Edwards, who lays down a beauty of a groove tail in the rhythm of an eighth-note and two 16ths (Ex. 6a). To emulate this groove tail, check out Ex. 6b for the static harmony and Ex. 6c for the mobile harmony.

The dotted eighth-note followed by a 16th-note is a groove-tail rhythm that’s surprisingly challenging to find. This rhythm is commonly used in groove skeletons (see Part 1 of this series, “Building Blocks of a Groove”), but not so often as a groove tail. James Jamerson to the rescue, with a splendid example in Gladys Knight’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” (Ex. 7a). Practice it with the default groove in Ex. 7b for static harmony and Ex. 7c for mobile harmony.

A truly unusual rhythm for a groove tail — but one that delivers a memorable kick — is the 16th-note followed by a dotted eighth, as played by the incomparable Pino Palladino on John Mayer’s “Who Did You Think I Was” (Ex. 8a). You can tackle the exercise version with the default groove in Ex. 8bfor static harmony and Ex. 8c if you’re going to a different chord.

The main purpose of the groove tail is to lead everyone smoothly to the top of the groove, which is why it’s rare to find one that has the challenging 16th-eighth-16th-note rhythm. However, when you’ve been playing with the same cats for many years and you’re comfortable with each other, and you trust everyone to hear when the groove comes back around, then you can certainly throw it in to make the bass part extra-interesting. John Paul Jones and his Led Zeppelin bandmates beautifully demonstrate how it’s done in the iconic bass part for “The Lemon Song” (Ex. 9a). You can work your own magic in Ex. 9b if you’re staying on the same chord or Ex. 9c if you’re moving into other harmonic realms.

Finally, there’s this other rhythmic subdivision: triplets! When your groove swings so heavily that it feels like you’re riding on a flat tire, in a good way! — for example, Tommy Cogbill’s line in Aretha Franklin’s “I Never Loved a Man” (Ex. 10a) — then you’d better do some preparing by running through the groove tails in Ex. 10b for static harmony and Ex. 10c for mobile harmony.

Even though the groove tail is always changing, even from one measure to the next within the same song, it’s crucial for it to provide a clear path, a guiding light if you will, to whatever follows. Despite the temptation to put your own flashy flurry of notes into the groove tail, think primarily of herding your fellow bandmates into the next phrase of the groove. I know, sometimes it’s like herding a bunch of alley cats, but that’s what we bass players do.